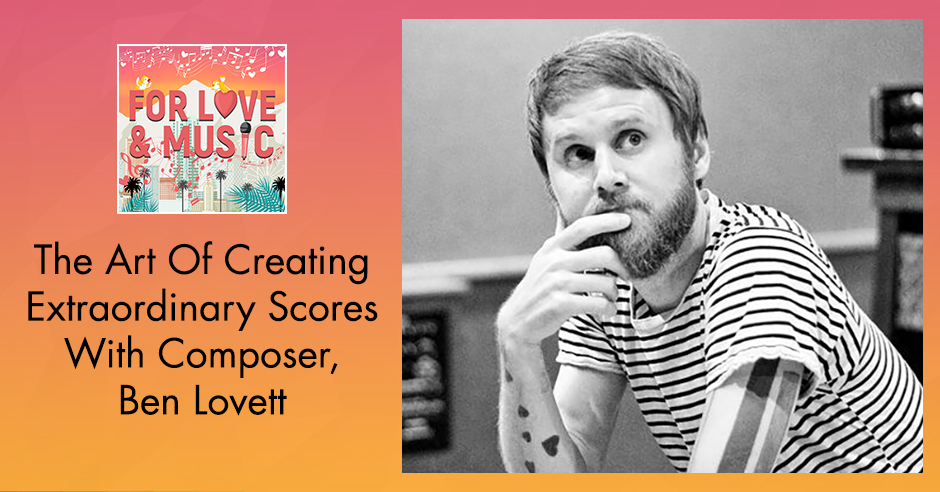

UNCONVENTIONAL AND EXTRAORDINARY SCORES FOR A DIVERSE RANGE OF FILMS ARE WHAT BEN LOVETT IS BEST KNOWN FOR. IN THIS EPISODE, BEN SHARES THE STORY OF HIS NON-MUSICAL BACKGROUND AND SUBSEQUENT RISE TO SUCCESS. HE DISCUSSES HIS MUSICAL STYLE AND THE PEOPLE HE ADMIRES AND LISTENS TO. HE ALSO TALKS ABOUT HIS VARIOUS PROJECTS AND CREATING THE MUSICAL SCORE FOR THE DOCUMENTARY “STUFFED“. BEN HAS CRAFTED ORIGINAL SCORES FOR FILMS INCLUDING , “THE RITUAL” ON NETFLIX AND THE DUPLASS BROTHERS’ SURVIVAL THRILLER, “BLACK ROCK”. HE ALSO EARNED A NOMINATION FOR “DISCOVERY OF THE YEAR” AT THE WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWARDS FOR HIS WORK ON “SYNCHRONICITY”.

—

Listen to the podcast here:

The Art of Creating Extraordinary Scores with Composer, Ben Lovett

Tara Joseph Interviews Critically Acclaimed Film Composer, Ben Lovett

I am excited about this episode’s guest. He is one of the leading American composers. Let’s welcome to the show the fabulous Ben Lovett. Ben, how are you?

I’m doing well. Thank you.

I like to ask everyone this. Where are you?

My studio is in Asheville, North Carolina.

I’ve never been to North Carolina. I’ve always wanted to go.

I grew up in Georgia. I would come up to North Carolina for summer camp when I was a kid and visit my grandparents who had lived up here. Later in life as an adult, I revisited. I’d been living in Los Angeles and bouncing between major cities and things for a decade or more. Something in me was yearning to reconnect with something like that. I ended up fleeing the city and posting up out here for the last few years.

Do you find as a composer that being in the environment that you’re in helps your creative juices flow more freely?

Yes, I have found it to be a conducive atmosphere for my own creative output. For much more boring reasons, yes, it’s beautiful and the air is cleaner, but it is a matter of being in a small town. The simple things are simple and the easy stuff is easy. It frees up a lot of mental bandwidth for other things that get sucked up doing mundane tasks when you’re in a city and I have a life. Here, I have no life. I just work so it’s quite convenient.

It sounds like the perfect environment. We’re all going through a situation that is unprecedented. I do hope that the world finds itself in a better place. How has your life changed since we went into the coronavirus pandemic of 2020? How has your life as a composer changed around those situations?

If you don't know anything about making a movie, why should you be afraid of making music for one? Click To TweetOn the surface, only a little. All the projects I’m involved with are all in post. They’re all shot. It’s not like a production that got shut down or canceled as a result. The things I’m working on are all at the stage where it’s people sitting in rooms, grinding away on it in post-production. Nothing has stopped or slowed down, nor has it in my process with the exception that I have found this all profoundly distracting. It has been difficult to focus or be creative because of the gravity of the situation and how much it pulls your attention away. How else are you supposed to respond when going through something that none of us have ever experienced or been through? Beyond that, it’s been the complete absence of other musicians available to bring into the studio, do a large session or anything like that. It’s changed a bit. On the current project, I had to recalibrate the idea of what I was going to do for the score into something I could mostly play myself in the room that I sit in alone every day.

It was a mentally challenging time for all. Did you always want to be a composer? Or is it something that when you were a child, you were surrounded by music? How did it all begin? Take us back to the beginning.

The answer is no. The earliest couple of memories that I have that are musical ones are when my dad would air drum to Beatles songs. Like in the car, he would play drums on the steering wheel, play the Ringo drum fills across the dashboard and slap the rearview mirror for the crash cymbal. I was a little kid. That was the foundation of my understanding of the basic principles of rhythm and music. My other one is going to church with my grandmother. I grew up in a rural part of Georgia. She would take me to this little country church out in the sticks where there were maybe twenty people. They would all sing hymns the entire time.

Between singing hymns in church with my grandmother and my dad playing drums on the steering wheel, that was my music education, until I discovered punk rock and hip hop as a teenager. I got into making music as a means of personal expression. It was a clumsy entry point of getting an electric guitar and a drum machine with some pedals and making noise. That was how I got into it. I don’t think that composing for film or anything like that was anything I’d ever thought about or considered. I never grew up in an environment where things like that seemed like it was an option.

What was the first score you composed?

I was at the University of Georgia in Athens and I was about nineteen years old. I met a group of kids in college who were all about a year older. I went to this party with my neighbor in my freshman year of college. She introduced me to this group of people and they were all having this party to celebrate this film project they were going to make. This was in 1997 or 1998. I met this group of people who were rallying together under the banner of this creative project and I wanted to be involved with it. My friends suggested to these kids, “You should get Ben to do the score for your movie.” I was terrified by the prospect of that. It was only two years earlier that I had bought a guitar and tried to figure out how to make a bunch of noise with it. I didn’t know the first thing about trying to score a movie or do 70 minutes of music for a narrative project or anything. I tried to convince him that was a terrible idea.

The director of the movie checkmated me with the logic of, “We don’t know anything about making a movie so why should you be afraid of making music for one?” I realized that he had me with that. I jumped on board. It was more about wanting to belong to a group or be part of something bigger than me. There was something exciting about that as a nineteen-year-old kid. I got involved in this project. We made this movie in college that no one will ever see or know about. We’d have parties and invite people over to show the movie. The point was just to make it. The only reason to do it was to finish it. That was the entry point. It was the first movie I did. I tell that story a lot like an origin story for this because it’s true, but I’ve realized over time that it was the foundation of my whole philosophy. It’s not just composing, but life in general, and certainly with its relationship to art. I try to never let the fear of not knowing what I’m doing get in the way of giving it a try anyway. My whole life and career have been learning on the job experience.

How would you describe your sound?

I’m not a band. I’m an artist. I’m a guy. I’m one person with ideas. I write songs and I sing. Those songs tend to be different based on who I might be in the studio with recording that particular song. The scores are like that depending on who I’m collaborating with, whether that be the director with the kinds of sounds and score they want for their movie and the musicians that I bring in to work and record with. The sound tends to take on some of the personality of these collaborators. That’s, for me, the most exciting part about the whole process.

Never let the fear of not knowing what you’re doing get in the way of just giving it a try anyway. Click To TweetI’m always trying to get away from whatever my sound is. I write songs and then come up with a sound as a way to express those songs, not the other way around. It’s not that songs are a vehicle for the sound that I make. I hope that the scores are that way too. The interesting part about that is every time I’ve tried to make that argument, people who have known me for a long time are familiar with the body of work I’ve made over the last years will always counter that. They go, “You have a thing that you do.” I’m like, “Every score is so different.” They’re like, “That’s true but there’s still a thing that’s you in there.” I can’t hear that in the way that other people can.

When I read your bio, it says you’re best known for crafting unconventional scores to a diverse range of films. Would you say it’s unconventional?

I don’t know. A publicist wrote that. It’s hard to say these days that anything is unconventional because it’s all relative. What may be unconventional to what one is familiar with may be typical or standard for someone else that watches more unconventional films.

You’ve got some great credits like The Ritual on Netflix, Sun Don’t Shine, Independent Spirit Award nominee for The Signal, Synchronicity, which earned you a nomination for Discovery of the Year. It’s some seriously great credits.

I’ve been fortunate to have attracted some interesting projects and some dynamic and talented collaborators. That’s the difference.

You’re still in the throes of your career. You’re fairly young from what I can gather so you have years ahead of you. Are there specific directors that you would love to work with, that you haven’t worked with yet?

Anyone I’ve worked within the past that I had a good experience with, I’m always looking for an opportunity to build on those relationships. You learn so much about the people you work with by the end of a project. You always hope to be able to have an opportunity to reapply that. By the end of something, you have a good sense of how to get to what they’re looking for. I have friends and people who I know and have developed personal relationships with that are doing well and would love to work with. They know who they are. It’s such a relationship-driven experience. I do work with a lot of people who I’m meeting for the first time. With the nature of these film experiences, sometimes the process can be so rushed and manic.

Generally speaking, the part that I’m primarily engaged in is a part of the process where the director is tending to a lot of different spinning plates at one time. They might be dealing with sound design, visual effects, color and post at the same time that they’re dealing with music. It’s the opportunity to get to a deeper stage of that collaboration that I’m always interested in. Beyond that, it’s not about the people as much as it is about the stories. I’m always driven to try to work on a different kind of story. Not so much in terms of genres where you break it down into the film logistics of it. I mean the types of stories. There are so many. That’s what my job is, an extension of the storytelling.

Are there composers who inspire you? It could be from the past or present.

I grew up as a kid in the ‘80s so all the John Williams stuff is probably as responsible for my love of this particular art form as anybody who does it. It’s a stock answer, especially for anybody that grew up in that era. There was something seminal and fundamental about all of that work that he was doing during that decade for a lot of people in my generation. That said, I don’t aspire to do anything like that or similar to what he does. I think that maybe the feeling that it gave you to hear the themes in those films kick in, as a young person watching movies, a foundation was set there that I didn’t fully realize until much later in college. I came across Peter Gabriel‘s score for the Last Temptation of Christ. It blew my mind. It’s still probably my favorite single piece of work that I can most consistently put on and be transported away, forget about everything, and be completely and wholly swallowed into this gorgeous work. I like all the stuff that Hildur is doing. I like Mica Levi’s stuff.

Hildur’s done brilliantly. Didn’t she win a Globe and an Oscar?

Yeah, she’s been doing great stuff for a long time. She was a longtime collaborator of Johann Johannsson. She’s been around and it’s cool to see her have such a cool, creative approach to how she does stuff. I think Mica is the same way. Mica has a cool approach to the projects that she takes and she’s picky about the stuff that she takes. Those are a couple of people who I like and have been listening to.

I’m fascinated by your project, Stuffed. Tell us everything because it’s extraordinary. The music is brilliant. Tell us how that came about, what it’s about, and what you’ve learned. I’ve learned stuff that I had no idea about.

Stuffed is a documentary that explores the delightfully bizarre subculture of taxidermy around the world and the artists that populate that particular subculture. Taxidermy is something that I knew little to nothing about going in. I didn’t expect to even take the job. I wasn’t even expecting that I would have found it that compelling. It is remarkable how quickly you realize that you don’t know anything about this world and how it is a profound and astounding area of art. It strangely doesn’t seem to have the same prestige that other art forms do, yet these people who are the leading taxidermists in the world are artists and scientists in one hand and the other. The nature of the work is so compelling, detailed, and intricate. I learned so much about it. What surprises you is that the one thing that they all have in common, the people who do this work, is that they all love animals. They’re huge animal and nature lovers. Growing up in a rural part of the southern states of America, my experience or relationship to something like taxidermy was going to a friend’s house and their dad would have a deer head mounted on the wall. That was pretty much it. That was what I thought it was. You realize that that’s part of it but it’s a small part.

For the readers who haven’t seen Stuffed, is it people who are sad their pets have died? Is it people who have a love of animals? What sort of people are doing this? Explain to us how you got your inspiration to create the amazing score that you created.

The one thing all the people who do this have in common is that they were probably the weird kid from their school growing up. They had an odd fascination and weren’t creeped out by the idea of handling dead animals. While most people think that makes them more like a mortician, that’s not it at all. The interesting thing about these personalities that you meet in the film is you realize that there’s such a variety of political, social and economic backgrounds that these people have. They’re people who probably disagree on politics and art outside of taxidermy and everything else under the sun. They all have this deep genuine love for nature. They all have this childlike wonder that’s distinct and comes through when they’re talking about how much they love animals. That was an endpoint for me as a point of inspiration. I realized that it’s a love story. It’s a movie about passion. It’s a movie that is trying to break down the stereotypes and misconceptions that might persist about these folks.

I thoroughly encourage everyone to watch it because I certainly learned a lot. I had a different outlook on taxidermists until I saw the program. I’m a big animal lover as well. I’m not sure I would have my dog or cats transformed by a taxidermist. I do understand the art behind it, having watched the show.

It is not who you know, but who knows you. People know you by being aware of what you're doing. Click To TweetI asked that question because a lot of people have asked me that question about the pets. Almost all of them will not do pets. It’s an interesting bit of ethics that come into play. A lot of professional taxidermists will not do pets, but not for reasons that you think. A lot of them came out to the premiere. I had an opportunity in some of the screenings to meet and get to know some of the people who were in the film. The answer from it seemed to be two things. One, as a person whose job this is, it’s an impossible gig.

There’s no way to ever get it right for the person who’d be hiring you to do it. They think that they’re probably contributing to the inability to let go of the pet. They also feel like that’s not a healthy function of the work that they do. The relationship that people had with the pet was when it was alive. As much as they can capture a certain spirit and essence of a particular animal, that might not be that animal. They can do a bear as a bear or an otter as an otter, but not your dog as Sammy. They can’t capture the personality of an individual animal or pet that embodies a relationship that a person would have with it. They can give you a tiger in the wild exhibiting all the personalities of a tiger. Beyond that, it gets so specific that it would almost be impossible to do.

When you’re presented with a project like this or another project, are you sent the script first? What’s the A to Z process for you?

That changes and it usually differs based on when the project comes across my radar or when the particular party involved reaches out. On Stuffed, it was unusual because they brought me on at the beginning of the project. The director, Erin Derham, reached out to me at the start of the project and said, “I want you to create music at the beginning.” This is as opposed to other films and narrative type films where oftentimes they’ll already have the film cut and edited or at least be in the process of editing. At the very least, they’ve shot the film before they bring a composer on board. With Stuffed, she wanted me to write music early so that the music could help inform how they edited the film. I remember her telling me that she wanted to make a movie about feelings, not facts. She didn’t want it to be this instructional documentary.

It was not a black and white thing she was trying to make. She had a specific perspective and angle that she was trying to take on the art form and a certain feeling that she wanted to embody. I started writing music before I even started seeing footage because they were in the early stages of filming. It took them two years to make this movie. Periodically, I would come back on board in between other films. She would send me little bits of footage. They would discover a new character and then they would go to Sweden to film them and then they’d go to the Netherlands. They’d find this guy in Iowa and they go up there and film that. They went to South Africa. As these new characters started to become part of the story, I would get little glimpses of these different personalities. I would be able to digest that and create different little sweets and pieces of music that I would send back to the director and the editor. They ended up sort of cutting the film to these musical pieces.

This film wasn’t a traditional documentary or narrative structure where we’re following the evolution of this one story. I realized that the score didn’t need to have this one cohesive movement or sound to it. The film is a lot about taking a peek into these different people’s lives and meeting these different characters. It’s seeing all these different perspectives on the art form and how they differ and how they’re the same. Somewhere in all that, I started to realize that the score was going to be this series of vignettes. I like to call them musical dioramas. The soundtrack, when you put it on, and the music in the film is a bit like walking around in a natural history museum, looking into different little displays. “Over here, you have a polar bear on an iceberg. Over here, you’ve got a deer in the woods. Over there, there’s a fish underwater.” That’s the way the music feels to me in this movie. Each one has its own little kind of frozen moment of a different habitat and a different creature.

It’s fascinating to hear how you work, the process behind your work and see the evolution of what you create. Are there any tips and pieces of advice you could give to any of our younger audiences out there who may be interested in becoming a composer and working in the film and TV industry such as yourself? I’m sure they’d love to know.

It’s getting your stuff out there where people can find it. They say it’s who you know, but it’s not true. It’s who knows you. People know you by way of being aware of what you’re doing. You’ve got to challenge yourself to finish ideas and to put them out. The best piece of music that’s still in your head doesn’t mean anything for your career or your pursuit of this as a life. The worst thing you managed to finish and put out is still more substantial and significant in that regard. You want to finish things and don’t be afraid to put things out and share things. Don’t hoard your good ideas because you’ve got to be able to come up with lots and lots of them. It’s just good practice to finish stuff and get it out there where people can hear it. Offer it to people to use in their films. Don’t think that talent is going to be the difference in your career path because it’s not. That part is too subjective. Everybody doing it is talented. It’s more about how hard you’re willing to work.

Ben, thank you so much. You’ve been an amazing guest. I’m happy you were able to come on to La La Landed. I’m excited for the audience to read all that you have to say. Stay safe and healthy. I am wishing you loads of luck for the future.

Thank you, Tara. I appreciate it. Thanks for having me.

Important Links:

- Ben Lovett

- Peter Gabriel

- Hildur

- Stuffed

- La La Landed

- http://www.BenLovett.com/

- https://www.Instagram.com/benlovett/?hl=en

About Ben Lovett

He is an American songwriter and composer best known for crafting unconventional scores to a diverse range of films and documentaries including the Netflix cult favorite THE RITUAL, Amy Seimetz’s award-winning noir SUN DON’T SHINE, Independent Spirit Award nominee THE SIGNAL, the Duplass Brothers’ survival thriller BLACK ROCK, Emma Tammi’s avant-garde western THE WIND, and the time travel sci-fi noir SYNCHRONICITY which earned Ben a nomination for “Discovery of the Year” at the prestigious World Soundtrack Awards. Lovett’s newest work include the colorful STUFFED, a documentary exploring the strange and unique lives of professional taxidermists, and Jim Cummings’ upcoming tragicomedy THE WEREWOLF. His most recent score debuted at Sundance 2020, a reunion with director and longtime collaborator David Bruckner for the upcoming Searchlight thriller, THE NIGHT HOUSE.

He is an American songwriter and composer best known for crafting unconventional scores to a diverse range of films and documentaries including the Netflix cult favorite THE RITUAL, Amy Seimetz’s award-winning noir SUN DON’T SHINE, Independent Spirit Award nominee THE SIGNAL, the Duplass Brothers’ survival thriller BLACK ROCK, Emma Tammi’s avant-garde western THE WIND, and the time travel sci-fi noir SYNCHRONICITY which earned Ben a nomination for “Discovery of the Year” at the prestigious World Soundtrack Awards. Lovett’s newest work include the colorful STUFFED, a documentary exploring the strange and unique lives of professional taxidermists, and Jim Cummings’ upcoming tragicomedy THE WEREWOLF. His most recent score debuted at Sundance 2020, a reunion with director and longtime collaborator David Bruckner for the upcoming Searchlight thriller, THE NIGHT HOUSE.

https://waterfallmagazine.com

Have you ever considered creating an e-book or guest

authoring on other blogs? I have a blog centered on the same

topics you discuss and would love to have you share

some stories/information. I know my audience would enjoy your work.

If you are even remotely interested, feel free to send

me an e mail.

Thank you so much.